Come, let us harken back to the Spring of 2003, a time of peace and prosperity (provided you didn’t catch the original coronavirus… or live in Iraq… or were a pyrophobic Rhode Islander whose favorite band was Great White).

During this revered era of harmony and abundance I was gifted sage inspiration by two different persons of distinction who were busy recording two very different records in my garage. Coincidentally, both people were drummers and both were respected for their penmanship.

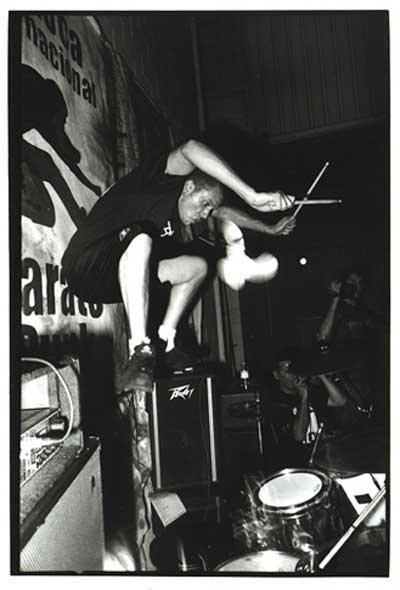

Max studying Japanese labor unions of the 18th century. Photo: Eric la Roca

The first inspirator was Max Ward.

But let’s back up even further to the day when Max called me and asked if I could bring my 4-track recorder to his practice space. He had a new band (not to be confused with his numerous other bands) and he was hoping I could record them, presumably before they broke up to form four new bands. As my luck would have it, that band turned out to be Scholastic Deth and within a month every Punk/Thrash/Hardcore/Grind band on the West Coast heard that demo and wanted their next record to sound just like it. Of course, this had little to do with my primitive engineering abilities and almost everything to do with Scholastic Deth being, like, hella good. Be that as it may, Max was now single-handedly responsible for me starting a recording studio.

Now fast forward back to 2003 to that studio, a one-car-sized box that he, Robert and I built in my two-car garage. Inside this unventilated fart trap we called The Dutch Oven, our band set out to record a new record, to the immense delight of my roommates, I assume.

[I would like to note that prior to this attempt we – and every underground band in the Bay Area – recorded almost exclusively with Bart Thurber at House of Faith. But demand for studio time with Bart was such that he would book a year’s worth of sessions in a single day, a day that bands would find out about beforehand and studiously mark in their calendar. And it was likely Bart’s unavailability that pushed us to record by ourselves in my garage, far from the competence and class A gear and potential for car theft provided by House Of Faith. Also worth noting was that Bart had three rules in his studio, one of which was specific to me – 1) “If Bart’s around, don’t make a sound” (meaning don’t hit your snare or crank up your amp when he’s busy mic’ing it); 2) “If you see Bart, do not fart” (a rule we flagrantly – and probably conflagrantly – violated); and 3) “Craig gets to ask one question per day” (because I would otherwise derail the session with an endless series of gear-geek questions).]

So, taking the lessons that I learned from looking listening over Bart’s shoulder all those years, I worked to bring the mix of our recording to what the band collectively celebrated as “good enough, I guess.” Its sonic makeup was surprisingly close to so many of the thrash records to which I grew up listening, and that stoked the 14 year old kid in me. Max, however, played it back repeatedly before finally instructing me to “mess up the drums.”

“What?”

“I don’t know, turn them down or something.”

And so I did, and I’ll be damned if the recording wasn’t made suddenly more interesting. It had more…character? Perhaps by appearing semi-unfinished the record ended up feeling more urgent? Whatever the case, it was ultimately made better by this illogical suggestion. And I came to learn that Max – who has released nearly 300 records in his day and who therefore knows his shit – was fostering a winning philosophy that went something like this: if it sounds good you are doing something wrong and it is your obligation to “mess it up.”

That same month, another drummer with a Discogs-defying track record, Aaron “Cometbus” Elliot, also said something that made me reevaluate everything. We were finishing the mix of what we eventually called “Colbom” and, once again, I had worked myself deaf trying to make everything sound as clean and balanced as possible. But Aaron had other ideas, starting with never using the word “clean” to describe one of his bands/recordings. In fact, in the middle of this session he brought me a DAT of one of his numerous other bands’ recordings with the hopes that I had the technology to “I don’t know, dirty it up.” (What is it with drummers being in too many bands and not liking things to sound too good?!?)

Aaron using the photocopier for the next issue of his zine. Photo: Sabrina VillaSenor

For decades prior to this session Aaron reliably showed up to shows and recording sessions with his unreliable drum set. While his playing is intense, energetic, and now a genre unto itself, bands like Crimpshrine, Screeching Weasel, Green Day, and Pinhead Gunpowder at one time all had to build their sound on his shaky foundation of a drum kit. He never changed a head, never fixed a broken lug, never replaced a cracked cymbal unless absolutely necessary.

And apparently recording a record was still not a sufficient enough reason to do so. After trying unsuccessfully to get what I thought were good tones out of his kit I suggested we use mine which at least had stands that wouldn’t fall over. He declined, stating that he wanted any kid to see him with his dilapidated drum set and think to themselves, “I don’t need good gear to play in a band.” It is an admirable intention, to be sure, but I pointed out that no kid was going to see him or his kit in my studio.

“They’ll know.”

So I shouldn’t have been surprised when we got to the mixing stage and Aaron did everything he could to make the drums sound even worse. We didn’t simply avoid standard mixing tools like EQ or compression, we consciously went in and made the drums sound, in a word, bad. I quickly realized he had much stronger feelings about the mix than I did and, like Max, his illustrious past coupled with my green studio skills ultimately lead me to follow his direction.

And sure enough, this recording stands as one of the proudest releases in my discography.

To be clear, I love both of these guys deeply even though what I’ve just described might make them both sound like weirdos. (Hey, at least I never called them bass players!) Aaron is fond of saying “I’m a drummer, not a musician” and Max once laid into me once for calling what we do “art” so I call them weirdos out of respect and reverence for their unique yet passionate perspectives towards their craft.

This guy sang for both of these bands and was also the best man in my wedding, so why not also share a picture of him?

Heck, while I’m mentioning both What Happens Next? and my wedding, I might as well also include a picture with Robert.

In conclusion, recordings that might be viewed as fucked up can, in fact, be charming. They have character. They’re human. A lack of glossy veneer is often offset by a spirit and authenticity. It’s, like, a vibe or something, man.

This bold approach to mixing a record (or even a song) is not without precedent. Many artists have gone their own way with an inexplicable mixing decision and made something unique in the process. A few that come to mind, for better or worse, are:

Tones on Tail “Go!” (that bass!)

Led Zepplin “When the Levee Breaks” (only two mics on the best drummer in rock history?!)

Prince “When Doves Cry” (one of the best selling dance artists of all time makes a dance song with no bass?!)

Beastie Boys “What You Want” (lo-fi madness)

Outkast “Speakerboxxx/The Love Below” (a true genre-breaker)

Metallica “St Anger” (when I mentioned “for better or worse” the snare on this record would qualify as “for worse”)

But not even these songs stuck out to me as much as the first time I heard The Stooges’ Raw Power record. How could such a seminal band have achieved such esteem and success with such a shitty recording?? Upon closer inspection they had an earlier record which I also checked out, called Fun House. It was not as bad but I would in no way describe it as a hi-fidelity recording, not when bands like Queen and The Who were perfecting the art of recording at this same time.

My first – and not unreasonable – thought was that everyone within 200 yards of the studio was high out of their goddamn minds. But in reality producer Don Gallucci made a deliberate choice in constructing and emphasizing the Fun House mix that made it to vinyl. His rapid realization after recording them “properly” was how much that pristine attention to detail absolutely murdered the feeling of what it was like actually seeing The Stooges play live. So Don decided to “mess them up” as Max and Aaron might say.

But that still doesn’t explain why their next record, Raw Power, sounded especially bad – particularly when you see “Mixed by David Bowie” in the liner notes. Sure, Don set a template for what a band like The Stooges could get away with on record, but if you’re bringing in David Fucking Bowie for your next project one would expect something at least as good as your previous effort, mias non…

In Bowie’s defense, it turns out that he was only given a 3-track recording to work with: ALL of the backing tracks (drums, guitars, bass, percussion, keys) were already bounced down to one mono track, while some guitar solos were on a second track, and all of Iggy’s vocals were on the third track. So really, there wasn’t much Bowie could do with it and it is generally believed that he managed some real magic under the circumstances.

But surrounding all of this lies an inconvenient truth – a band only needs one of the three following attributes to cut a deep mark into pop culture:

* musical talent

* brilliant song

* excellent recording

Sadly, having all three of these qualities still doesn’t procure you a place in my music library, but it is interesting how many of my absolute favorite, most listened-to records only have one of these elements.

Anyway, here’s my version of a song from one of those Stooges records…

(Before you ask – Yes, I got that mole checked out and I’m good, and it took my about four days to get all of that peanut butter off of me.)

Download/Listen here:

Craig Billmeier

Craig Billmeier

Post a comment